Climate and energy analysis of BCI’s 2024-2025 Stewardship Report

On September 16, the British Columbia Investment Management Corporation (BCI) published its 2024-2025 Stewardship Report, reaffirming its commitment to climate stewardship at a time when some institutional investors are scaling back ESG priorities amid political and market headwinds. Unlike peers that have softened their climate positions, BCI has remained vocal about the financial materiality of climate risk and the importance of robust policy frameworks to support the global transition. Climate change remains one of just three top engagement priorities for BCI (p. 5). BCI highlights its company-level engagement and climate policy advocacy, demonstrating an understanding that investors can have influence beyond their portfolios and help shape the rules that guide the market toward decarbonization. The investment manager continues to articulate that physical and transition risks can significantly impact asset valuations, increase operational costs, disrupt supply chains, and lead to stranded assets (p. 5). Despite its ongoing engagement and stewardship efforts, BCI’s approach is insufficient to drive change at the pace required by the climate crisis.

BCI’s role in shaping climate policy

BCI participated in 22 ESG-related policy consultations (p. 7). Policy advocacy is an effective tool for systemic change and an essential component of strong climate stewardship. Strong, science-based climate policy helps provide the regulatory certainty investors need to allocate capital to low-carbon solutions and ensures that carbon-intensive sectors decarbonize in line with global climate goals. Compared to many of its peers, BCI takes a more active role in shaping the policy environment, participating in consultations across multiple jurisdictions and advocating for global adoption of the ISSB standards to improve the consistency and reliability of climate-related disclosures. BCI has consistently advocated for mandatory, standardized ESG disclosure, stating, "BCI strongly believes the ISSB standards should be adopted globally. Access to quality, comparable ESG and climate data is integral for investors to make informed decisions" (p. 7). Through submissions to regulatory bodies in Canada, Korea, and Japan, plus collaboration with other Canadian pension managers, BCI contributed to progress where "At least 35 jurisdictions covering 40 per cent of global market capitalization and 60 per cent of global GDP have now incorporated these standards" (p. 7).

BCI also commented on the greenwashing provisions in the federal government’s Bill C-59. BCI argued the provisions had the unintended consequence of prompting companies to withdraw sustainability disclosures and urged the Competition Bureau to differentiate between corporate marketing materials and data-driven sustainability information for investors (p. 7). Following the law's enactment, BCI pursued direct engagement with Canadian energy companies that had removed publicly-available sustainability disclosures, requesting timelines for reinstating them (p. 7).

BCI's expectations for companies would be stronger if backed by its own net-zero commitment

BCI expects portfolio companies to adopt net-zero commitments, stating that it “is committed to ensuring at least 80 per cent of our most carbon-intensive investments have mature net-zero targets by 2030" (p. 17). However, BCI has not yet set a net-zero target for its own portfolio.

The absence of BCI's own net-zero commitment creates several challenges. BCI's ability to push companies toward ambitious climate action would be strengthened if the pension manager made this foundational climate commitment itself. BCI "pays close attention to the disclosures, targets, and practices of (its) most carbon-intensive investments to assess the maturity level of their net-zero plans" (p. 12), yet does not subject itself to the same standard. A portfolio-wide net-zero commitment would also create clear metrics for measuring BCI's own progress.

Additionally, without its own net-zero commitment, it remains unclear whether BCI will require the managed decline of production by oil and gas producers in its portfolio, even though this is the only pathway to Paris alignment for such companies.

The timeline for engagement and escalation remains unclear

BCI has established some clear climate-related expectations for companies, but provides limited transparency about timelines for achieving those expectations and consequences for failing to achieve them. BCI discloses some escalation strategies, stating that "In cases where companies are not progressing toward our expectations, BCI may vote against the board chair, lead independent director, or chair/members of the sustainability committee" (p. 12).

But the stewardship report does not specify by when companies must demonstrate progress, how long they remain in the "neutral" category before further escalation, what the consequences are if voting fails, or whether divestment would ever be considered. This ambiguity is particularly concerning for fossil fuel holdings, where credible decarbonization pathways require the rapid phase-out of production and early retirement of assets to align with Paris Agreement goals.

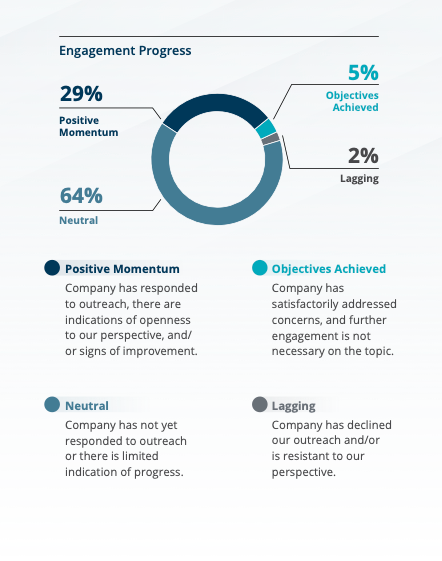

BCI also disclosed high-level numbers about its engagement outcomes:

5% of companies achieved objectives or addressed engagement concerns;

29% responded to outreach, showed indications of openness to engagement or signs of improvement;

64% were rated “neutral” (company has not responded or shows limited progress);

2% declined BCI’s outreach and/or were resistant to BCI’s perspective (p. 14).

This means that nearly two-thirds of companies have either not responded adequately or shown limited progress– raising critical questions about the effectiveness of BCI’s engagement efforts.

BCI does not disclose which companies are lagging or rated neutral, or how many of those companies are lagging when it comes to climate in particular. BCI’s emphasis on "patient, constructive dialogue" (p. 12) may be effective in some engagements, but when looking at high-emitting companies like fossil fuel producers, an indefinite timeline is concerning. Fossil fuel companies do not have viable transition plans, and if BCI is continuing to hold onto those companies in order to engage them, that’s valuable capital spent on companies causing the climate crisis that could instead be shifted to climate solutions.

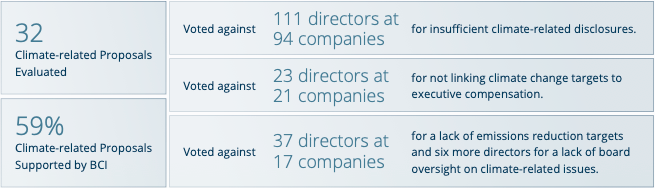

BCI updated and reinforced its proxy voting guidelines.

BCI released its updated proxy voting guidelines earlier this year, which incrementally strengthened BCI’s approach to some ESG considerations, including climate risk, transition plans, Indigenous rights, ESG-related training for company boards, and linking executive compensation to ESG performance. BCI “may” continue to vote against board chairs or directors at carbon-intensive companies failing to meet BCI’s climate expectations “or progressing towards doing so”.

The investment managers climate-related proxy voting record demonstrates some willingness to escalate—voting against 111 directors at 94 companies for insufficient climate disclosures, against 23 directors at 21 companies for not linking climate targets to compensation, and against 37 directors at 17 companies for lack of emissions reduction targets (p. 12).

However, the limits of proxy voting as an escalation tool are evident. BCI has been voting against directors at certain companies for multiple years without securing change or achieving credible climate plans. This raises fundamental questions for an investment manager whose mandate is dependent on a stable climate: is proxy voting actually an effective accountability mechanism, or primarily a signaling tool? When voting fails to produce results, what is the next level of escalation? How many years will BCI continue voting against directors at companies that fail to develop credible climate plans before concluding that continued ownership is inconsistent with its duty to pension plan members?

Without clearer articulation of what happens when proxy voting fails to effect change, as appears to be the case for the majority of engaged companies, voting risks becoming a symbolic gesture rather than an effective stewardship tool.

BCI achieved results through Climate Action 100+.

Despite its shortcomings, BCI’s commitment to engaging on climate is noteworthy given the headwinds facing ESG investing. BCI maintained active involvement in Climate Action 100+, where it leads or co-leads engagements with 11 companies (p. 17). Last year, Anne-Marie Gagnon, BCI’s Director of ESG, was appointed to the Climate Action 100+ steering committee (p. 17).

BCI’s collaborative engagement through Climate Action 100+ demonstrated examples of effective engagement. BCI's co-leadership of a seven-year engagement with Teck Resources stands as the most compelling success story in the report. In response to this focused engagement, between 2020 and 2024, Teck adopted net-zero commitments with interim targets, integrated climate metrics into executive compensation, advanced policy advocacy transparency, and launched a carbon capture pilot (p. 17). Most significantly, "the engagement culminated with Teck's divestment of its steelmaking coal business in July 2024, repositioning the company as a focused base metals producer of materials essential for the energy transition" (p. 17). Importantly, BCI frames the divestment of fossil fuel business lines as a desirable outcome, suggesting openness to strategic exits from high-carbon activities.

BCI also notes some broader successes as a result of Climate Action 100+: 80% of target companies are committing to net-zero by 2050 for Scope 1 and 2 emissions, and 90% of boards now have climate oversight (p. 17). However, many of the companies BCI engages through Climate Action 100+ are oil and gas companies, the majority of which do not meet any of Climate Action 100+’s benchmarks for net-zero alignment. Even Climate Action 100+’s 2024 Progress Update acknowledges that the oil and gas sector is not taking steps to shift to a clean economy (p. 5). While BCI may be seeing some new corporate climate targets, these commitments do not change the fact that fossil fuel companies simply do not have credible Paris-aligned transition plans.

BCI engaged financial institutions on climate disclosure.

BCI pursued enhanced climate disclosure from Canadian banks, with mixed results. The investment manager held dialogue with Bank of Nova Scotia's CEO on sustainable finance targets and Energy Supply Banking Ratio (ESBR) disclosure, reporting that "In 2025, (Bank of Nova Scotia) publicly committed to disclosing its ESBR, positioning the bank as a leader among its peers" (p. 15-16).

BCI also "supported a shareholder proposal put forward by the Shareholder Association for Research and Education (SHARE) asking the Bank of Montreal (BMO), Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC), and Toronto-Dominion Bank (TD Bank) to disclose their energy finance ratios" (p. 10). The resolution at TD received 38% support—"the strongest support ever recorded for a climate-related proposal at a Canadian bank"—while those at CIBC and BMO received 37% and 32% support, respectively (p. 10).

The report makes no mention of whether any of these three banks will actually comply with the disclosure request despite the historic shareholder support. The report also does not disclose what BCI's next step will be if these banks decline to provide the requested disclosure. In 2024, the energy finance ratio for the Big 5 Canadian banks was 61 cents going toward low-carbon options for every dollar to fossil fuels. This was a drop from the previous year, and lags behind the global ratio for banks of 0.89 to 1.

Strong climate stewardship, but more action needed

BCI's 2024-2025 Stewardship Report demonstrates institutional commitment to climate stewardship at a time when many peers are retreating. BCI has maintained climate as a top-three priority, contributed to climate policy advocacy, demonstrated leadership through Climate Action 100+, and shown willingness to vote against management that fails to make sufficient climate progress. Jennifer Coulson's message captures BCI's approach well: "Every engagement, every vote, and every policy submission is ultimately about protecting and growing the assets entrusted to us by our clients" (p. 3). BCI knows climate stewardship is not just values-based investing, but fundamentally part of fiduciary duty.

BCI is clearly among the stronger players on climate stewardship in the Canadian pension sector. But questions remain about what happens when engagement doesn't work, whether BCI will hold itself to the same climate standards it applies to portfolio companies, and whether its approach can drive change at the pace required by both climate science and fiduciary duty. This challenge is especially pressing for fossil fuel companies, which have no credible pathway to decarbonization other than the phase-out of production and early retirement of assets. BCI’s emphasis on “patient, constructive dialogue” (p. 12) must be weighed against the shrinking window for limiting global warming to safe levels and the mounting financial risks of a delayed transition.

Ultimately, the question for BCI's clients and stakeholders is whether the investment managers’ stewardship approach is sufficient to navigate these accelerating climate risks—or whether stronger commitments, clearer timelines, and tougher accountability measures, including divestment and exclusion, will ultimately be required.